Do you remember that feeling when Twitter first started working for you, and you were suddenly tapped into this seemingly infinite network of other people in your profession, who shared experiences and ideas and perspectives and guidance? What an amazing time that was; I absolutely loved it.

I got into librarianship in 2006, but it only really came alive for me in around 2010 when I got online. In 2011 I joined Twitter (thanks as ever to Bethan Ruddock and Laura Woods for persuading me that my doubts about it were misplaced!) and really everything changed. It led to all sorts of opportunities, but the thing I appreciate most about the platform is the sheer number of voices it has allowed me to hear - I got so many useful insights I wasn’t getting within the walls of my own institution. My eyes were opened, my knowledge was expanded, my politics moved even further to the left and I changed. Twitter changed me, for the better.

Twitter is now untenable

However, since Twitter became X it has become untenable and it is only the sheer power of the relationships I built over 12 years that has kept me there this long. There is no other brand or organisation run by a white supremacist that I would consider giving my time to; it feels deeply uneasy to be part of something so incredibly toxic, because you feel complicit.

I’m not deleting my account (yet) mainly because I don’t want anyone else using the alias, but I am officially leaving the site from Christmas - no longer logging in or posting. I wouldn’t presume to tell anyone else what to do but if you’re still there, I’d recommend at least considering getting out too.

Need some reasons to leave Twitter?

Hate speech, harassment, extremist content and misinformation have all spiked since Musk took over

Musk himself has said some abject things, including describing antisemitic conspiracy theories as ‘the absolute truth’, and threatened violence against his enemies

Musk has reinstated previously-banned white nationalists and whole host of incredibly toxic accounts which he’s now actively promoting, whilst deleting accounts of journalists he doesn’t like and reducing traffic to news sites

Honestly there’s just an endless list of things. Even just researching enough to list points 1-3 above is so bleak, I don’t want to do any more; every day there’s something else awful he’s done, just google his name and you’ll see the latest

So what happens next for libraries and librarians? Originally this one post about both those categories, but it got ridiculously long so I’ve moved the bits about libraries into a separate Part 2. Let’s focus first of all on us, the people working in the cultural orgs, which is the slightly less complicated side of the coin in some ways.

Social media for librarians, information professionals, and others who work in cultural organisations

So here’s a massive disclaimer about this section: it is VERY subjective. (The bit about libraries and social media in part 2 is far more objective.) It’s based on my experiences and my preferences. Your mileage may vary.

I have now been actively looking for and posting on Twitter alternatives for over a year, and this is what I’ve concluded. (tl;dr Bluesky is the closest equivalent to early Twitter, and I whole wholeheartedly recommend getting yourself an invite code if you can.)

Threads just isn’t quite happening for librarians

I wanted Threads to work, so I joined early and optimistically. I followed lots of library friends, plus a few larger accounts, newspapers and the like. And what I’ve found is, my feed is 90% posts from the Guardian etc and hardly any from the library people. (There is apparently loads of book-chat on Threads, but not so much library chat.)

Part of the reason for this is that Threads is unavailable in the EU. So the entirety of European librarianship, pretty much, is absent from the discussion. I love European librarians and want them in my network! [EDIT: since I wrote this post, Threads as become available in the EU! This may change everything and make Threads a viable network for librarians over time, we’ll have to wait and see.]

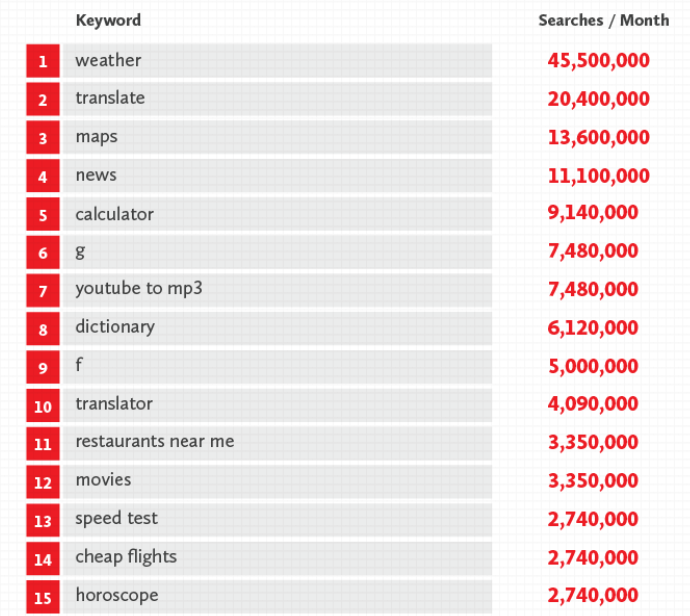

Threads famously became the fastest growing new social network ever: while Facebook and Twitter both took over 2 years to reach 10 million users, Threads took just 7 hours. There are now 137 million people with accounts - but that doesn’t matter. What mattes is active users. There are around 10 million active Threads users, who only spend 3 minutes a day on the app. (Obviously, 10 million is a large number - but compared with 200 million active Twitter users, or 2.35 billion active Instagram users, clearly there is simply less conversation to be had there.)

So my Threads account lies dormant, with a post basically saying: I’m putting my eggs in the Bluesky basket.

Instagram is essential for libraries but potentially less so for librarians

I enjoy Instagram but I am there as a drummer, not as a library professional. I do follow some librarians on there and enjoy their posts, but they tend to be about their lives rather than their work.

My experience has been that Instagram’s primary focus on video, then on image, and then on words, means it’s not as suited for a professional network in our particular profession (and a lot of info pros aren’t there on principle because it’s a Meta product) - but actually this is probably too limited thinking on my part. Naomi Smith is making the @blackandgoldeducation critical librarianship account work on Instagram, and points out:

There are many people, organisations who are interested / amazed by ideas of #critlib and share similar values especially younger audiences which is the main instagram demographic

LinkedIn is actually pretty good after all!

I have been so sneery about LinkedIn over the years, put off by some performative posting I saw in the early days, and the (rightly earned) reputation the platform has for being a home to the ‘I get up at 4am and have already done 3 workouts and boosted productivity in my companies by 6% by the time you have breakfast!! hashtag #stayhumble’ brigade. HOWEVER I was basically wrong, because like almost all communities, the thing it’s most famous for is not what it’s actually like for most people there.

Connect with the right people (oh hi!) and LinkedIn is a friendly, supportive place where you get useful updates about what is going on in the industry. It’s also a good place to share ideas, with decent numbers of people reading posts on there, and people actually leave comments and ask questions - posting on LinkedIn feels like blogging felt about 10 years ago!

The only downside is it’s almost all professional, and I love a little bit of personal mixed in - I want to know about who we all are as people, as well as what we achieve in our jobs. But basically if, like me, you’ve written LinkedIn off in the past, give it another go because you can be part of the good bit of it…

Mastodon is good, but it’s not quite the Twitter replacement I craved.

When I joined Mastodon I initially really enjoyed it, but several small things have meant that optimism was short lived. It doesn’t look great or feel that good to use - it’s a little clunky - and there’s well documented issues with finding people across the federated servers. There are also lots of examples of being people scolded for doing the wrong thing on Mastodon, though I’ve not experienced this myself.

More than that though, the biggest issue for me is I just find myself scrolling for a long time on the platform before I find content I’m interested in. The conversation just doesn’t quite seem to match up to what I need from a professional / social network mix - and that’s very much a personal thing so you might find the chat absolutely hits the sweet spot for you.

I had an interesting chat with a BlueSky user called Mx Vero who said Mastodon DID work better for them than Bluesky - in particular the code4lib.social server, which leads me to speculate that the info pros at the more technical end of librarianship are more likely to find Mastodon useful, because the are less likely to be put off by the technical hurdles to getting set up on the platform in the first place. So there’s a greater amount of conversation to be had in that area of libraryworld, on Mastodon.

Someone on Bluesky asked ‘why didn’t Mastodon work for ya’ll?’ and one of the answers was this:

“It felt a little like eating something because it was good for you but not something you enjoy”

This sums it up well: Mastodon has a great community but the vibe - I’m bringing out all the scientific terms now - is just slightly off, for me personally. Which brings us to…

Bluesky. I’m all in: Bluesky is the one.

I am only two months in to being part of this platform, but I really, really like it. It feels VERY twitter circa 2015 - not least in visual style as it is made by the same people who made Twitter in the first place, but just in terms of the way it feels and the conversations we’re having there.

The hit-rate of stuff I’m interested in versus total posts to scroll through is much higher than anything since several-years-ago-twitter, and there’s a real sense of a community sharing updates and ideas. It seems to have a good mix of serious and fun.

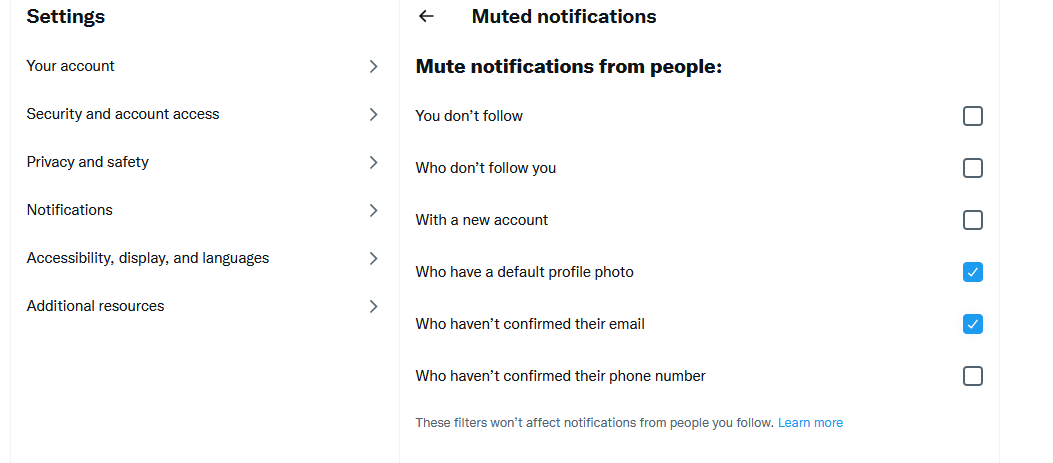

You need an invite code to join (which is part of the reason it’s not overrun by far-right people) - just ask on your other networks and chances are someone will message you with one. We all get one a week to give out to people. When you get there, say hi!

I asked others why it worked for them: Alice Cann said:

“I found library and related people here on BlueSky immediately and there are a core amount of people posting quite often”

Selena Killick said:

“Ease of use and the fact that Librarian twitter seems to have moved here has helped”

…and several others chimed in with similar views. Arianne H. said:

“Once I figured out how they work, I have found the feeds to be a really useful way to keep up with library related conversations, especially Skybrarians. I like that feeds are created by users.”

Feeds are, I think, like Twitter lists but intended as a much more public-facing thing rather than a personal one. Here’s the skybrarian feed link for those already on the platform - thanks to Andromeda Yelton for setting it up!

manu schwendener said:

“Best feature for me: that their roadmap and issues are public”

…and also has some useful guidance on first Bluesky steps, including using Follower Bridge to reconnect with your Twitter contacts. It’s a pretty manual process that will take a while if you follow a lot of people, and it’s a bit hit and miss (if you follow someone called ‘Dave’ on Twitter it’ll find someone at random called Dave on Bluesky and be like, hey I think we got him!) but a good jumping off point. As always though, a reliable way to jump start your community building is this:

1) Set up your profile - bio, pic, a first post - BEFORE you start following people, so when they get the notification of the new follow and potentially click on your profile, there’s something for them to see

2) Find a librarian you like, click on the list of people THEY follow, and canabalise it

On top of all that, the way the community is building organically is really nice. Threads felt like a mad rush, with everyone joining and then almost immediately leaving (albeit not deleting their accounts because you can’t without also deleting Insta), while Mastodon felt like a party that had already been going for a while before you got there, and has certain rules and norms you’re not fully up to speed with. Bluesky just builds slowly, and because you get an invite code per week to give out, people are gradually bringing others into the fold and more and more people we all want to see there are arriving.

Here’s the real test of which social network you most identify with - which profile do you put in your speaker bio and on your first and last slides..? I’ve changed mine to Bluesky. I’m all in!

What is the longer-term prognosis for librarian social media?

The answer to this questions is of course that I don’t know, but there’s a couple of things worth bearing in mind. One is that even if, say, something else comes along in two years that we all end up switching to, two years is a long time! Two years of being a networked librarian able to tap into support and ideas beyond your institution, even if imperfectly, is so much better than nothing. But the other thing is, I don’t think we’ll ever get another Twitter. Not in terms of the sheer focus of dialogue in one place - the world and the online landscape is too fragmented now, so we’ll split off into smaller communities.

I’d love to be wrong about this of course. But if we do end up with lots of options, the important thing is not to let that put us off. Pick one, try it, and see if it’s for you. If it’s not, move on. If it is, go all in. Because we’re all better off for having a way to benefit from our professional community online - I hope you find yours!