We’ll all be teaching infolit online for the foreseeable future (I hope) and it is, as anyone who’s done much of it will tell you, a very different experience to being in a room with people.

I do a lot of training online already for overseas audiences, so I have some familiarity with this. For what it’s worth, here are some tips for retooling your sessions to work in a webinar type environment.

Plan your session so your audience switches frequently between listening and doing

I don’t know how you currently do your workshops, obviously, but if for example you do a 20 minute intro, then give people 20 minutes to do a task or two, then 10 minutes summing up at the end, you may find it worthwhile to rejig this a bit.

In the online environment where everyone is learning on screen, too much of anything for too long is a barrier to engagement. Long talky bits are really hard to pull off, and long activities don’t often work either. And indeed, long sessions overall - if you had a 2 hour class booked, make it 1.5 hours max for screen-learning.

In my experience, relatively short bursts of talking interspersed with relatively short bursts of activity works best. So take a big exercise and split it into two; introduce part one, let them try it, introduce part two, let them try that. And so on. Short, sharp chunks. (Can you have sharp chunks? Shards, maybe.)

Mute participants (apart from specific times for questions)

I always, always have participants muted as they enter the online space. If everyone’s mic is live, it quickly becomes a cacophony of noise that makes it impossible for anyone to really concentrate. (Honestly just one person having a chat with someone in the same room is enough to derail things.)

I encourage questions at any time via the Chat (more on which below) rather than audio - however sometimes it can be beneficial for people to ask questions out loud rather than type them. If you want to do that, have a clearly designated time in the session when this will be possible, and signpost it ahead of time. “On 30 minutes we’ll pause, and anyone who wants to unmute and ask a question can do so then.” Then the conversation happens, everyone mutes again and you carry on from there.

If you do this it’s important to wear headphones, otherwise the audience’s questions come out of your PC speakers, into your mic, and back out of the speakers again - this causes all sorts of problems and is definitely best avoided…

Consider using your webcam for the intro, then turning it off

Assuming you have a webcam and video is an option, there’s a balance to be struck there too. Webcam-on for the whole session is, in my experience, not conducive to good teaching. You instinctively present to the camera, and this means you’re worrying about that side of things rather than your slides and the Chat. Especially if you’ve not done too much online teaching before, I’d keep things as simple as possible because there are so many more things to juggle than in an online session. You can choose to not use the webcam at all (that’s fine!), or use it for the intro and then say ‘now we’re moving into the session and using the slides, I’m going to turn off the webcam so you can see my screen better’.

This is because part of each slide is blocked by your own face with the webcam. I have done a workshop where for specific reasons the whole thing was camera-on, and I found it useful to work out exactly how big the camera-window would be and create a Shape in PowerPoint that was the exact dimensions. I then put this on every slide and made sure no content was going in that part, so nothing would be obscured by the window later (which I positioned over the Shape).

The Chat function is absolutely key

If you’re using webinar software then Chat will be a way your audience can ask you, and each other, questions. Confusingly there is also a Questions function in things like GoTo Meeting - and it’s really important to shepherd people toward Chat rather than Questions. Questions are only seen by you, but Chat is seen by all participants. Obviously if someone had a sensitive query, the DM-style Question is the way to go - but for everything else, you want to encourage active participation as much as possible. Often the difference between good online training and great online training is the Chat - the more people talk to each other and to you, the more than barriers of it being online fade away and the more useful the session becomes.

Whether you’re using Hangouts style software or webinar software or Google Q&A, it goes without saying you need to keep the Chat where you can see it at all times. You can have particular periods of the session when you dip into it and respond to what has been asked, but seeing the questions as they come in is vital for engaging the audience. Obviously if you have a second screen this helps a lot, but if you don’t have that option it’s still worth making sure the Chat is visible to you always.

I tell people about it at the start, and I remind them about two minutes later - I tell them about it again and again because sometimes people need encouragement to use it, but once they do everyone tends to join in. Teaching is so much richer when you respond to the audience’s specific needs, so it has to be a priority to make sure these needs are expressed…

Get used to not speaking

What separates good online teaching from boring webinars is interactivity. The Chat is key to this as discussed, but so is getting people to DO things and - trust me on this - it feels really, really, weird to give people time to do activities and exercises while you sit there in silence. But it’s better to have a couple of 5 or 10 minute activities where your audience are genuinely given time to try things out and then report back in the Chat.

I find this really tricky because you become hyper-aware of the dead air. You’re not wandering around checking what people are doing, you can’t see them working or hear them chatting to each other. You feel faintly absurd, sitting there in front of your PC and hoping people are using the time you’ve given them to do the thing you’ve asked them to do. But it’s essential - it stops it being a classic ‘boring webinar’, one-way traffic delivered as a lecture on screen which, even if you’re great at public speaking, is not enough to truly engage most audiences.

I find the not-speaking part so hard that I set a stop-watch for it every time. If I’ve told the group they have 10 minutes, I’ll start a stop watch and not stop them until 10 minutes is up. If I don’t take this measure, I inevitably get angsty 6 minutes in and then move things on prematurely…

I always mute my mic for these parts - no one wants to hear the click of your keyboard etc - but check in on the mic a couple of times during the period to say ‘don’t forget if you have any questions or something isn’t working as you’d expect, ask me in the chat’. When people ask a good question I’ll come back on the mic and pick it up with the whole group, just as I would with a face-to-face session.

You may wish to stand up…

Teaching needs energy, and sometimes it’s hard to bring energy when you’re sitting down! If your mic and other equipment allows it and you’re comfortable doing so, standing up to deliver your session just as you would in a seminar room can really help. Without hand gestures and facial expressions it’s already hard to get your point across dynamically, so your delivery counts for a lot.

Something solo radio DJs apparently do a lot is put something opposite them to stand-in for the audience - a cuddly toy or, in one studio I saw, a Policeman’s helmet - and they talk to THAT. Rather than talking just generally into the ether, addressing something specific (even something faintly ridiculous) will focus your delivery and make it more human. So grab some sort of mascot and stick it above your monitor…

If you can do online teaching in pairs, take that option

Managing an online session is quite stressful - if anyone has technical problems you really can’t help them and teach at the same time. So pairing up, with one person teaching and another facilitating, is well worth doing if you can. The Facilitator can be on hand to help participants, both with the logistics of the online session and with the exercises themselves - they can also message the presenter to flag up a Chat question if they miss it. Working as a team in this way allows you to teach better because you’re not splitting your focus.

Good slides matter more than ever

If you’ve read this blog before you’ll know I think good slides are important. In online teaching they’re even more so, because they’re the only thing your audience can see. It’s not just that they can’t see you; they can’t even see each other. So something inspiring on the screen is really essential - especially if your online session is coming as part of many, many other sessions also online. Death by PowerPoint will not do.

There’s plenty of guidance on this site about making good presentations. A couple of posts to start with would be the Alternatives to Bullet Points and the Sources of CC0 Images articles: but really anything with the presentations tag is potentially relevant.

Unbelievably this general guide to slide-making is 6 years old now, but although some of the links to image sources are out of date, and, frankly, I’d make very different font choices nowadays, the basic principles are still important for producing effective presentation materials!

Accessibility and online teaching

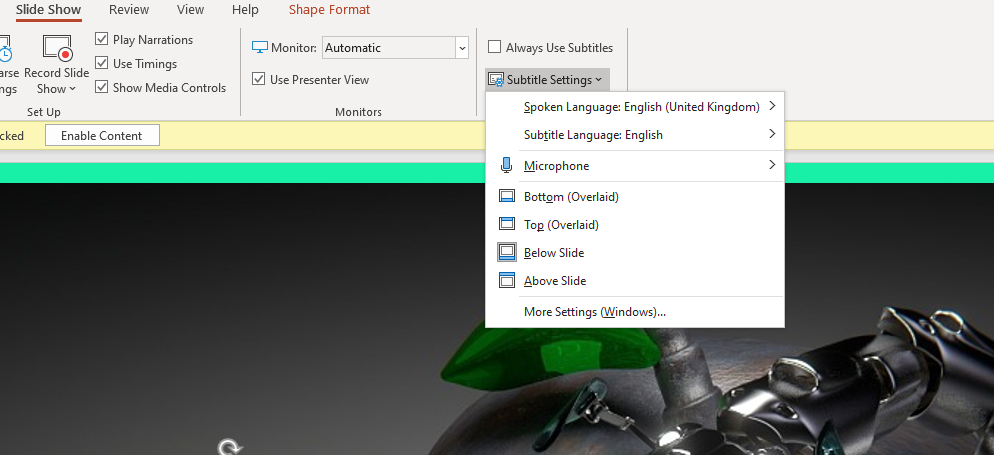

I don’t want to position myself as an expert on this but I do have advice on making your slides more accessible (thanks to Rachel fro the prompt!). The main thing is to use PowerPoint and turn on the subtitles function - if you’ve never used this you’ll be amazed at how well it works. PowerPoint provides subtitles of everything you say, as you say it. You can find the Settings for this in the Slideshow part of the menu:

Otherwise all the normal rules apply.

Good contrast between font colour and background. It’s important to have plenty of contrast, for example black text on white background, so the text is easy to read. Purple on black for example doesn’t work. Related to this, don’t put text over a busy background.

Minimum font size of 24. Anything less than 24 risks being hard to read on a small screen; if you need the font smaller than 24 there’s probably too much information for one slide.

Use sans-serif fonts. Sans-serif fonts such as Calibri and Arial are better than Serif fonts such as Times New Roman or decorative / script fonts.

Don’t use colour as the only indicator of key information. You will almost always have at least one colour-blind audience member. It’s important to avoid using colour as the sole way of conveying information. For example, to have something shown in red to say stop doing it and something else in green to say start doing that, is not sufficient. Use the text, or a tick and cross or other non-colour-based-visual indicator, to ensure people understand what you’re telling them.

Repeat Chat questions back. This is good practice anyway: if someone asks a question in the chat, say it out loud for everyone to hear before answering it.

There’s lots more aspects of teaching online that others will be able to go into in more depth, but the 8 things above are, to my mind, key as we #PivotToOnline (as they say on twitter…) Good luck everyone!

Any questions, tips, comments, suggestions, advice? I’d love to hear it in the Comments.